October 06, 2008 Categories: Reviews

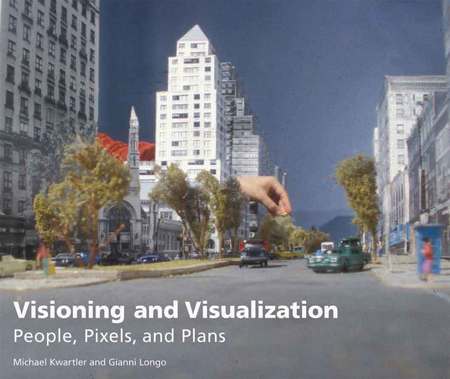

Visioning and Visualization: People, Pixels, and Plans

Michael Kwartler and Gianni Longo

2008. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. 94 pp. $35.

The ever-improving technology of real-time 3-D immersive visualization can give everyone a taste of the architect’s gift of being able to envision what’s not there yet. Specifically, these technologies can empower communities to determine their own future in more detail than ever. That’s the overall message of the new book by Michael Kwartler FAIA and Gianni Longo: these software packages can enhance public participation, not just in “visioning,” but in actual planning, design, implementation, and subsequent fine-tuning.

The fanciest software they describe allows you to “stroll” through a proposed neighborhood and “see” it as if you were there, and then allows you to change the neighborhood and see how the change looks and feels from “inside.” Similarly, it can be used to show, for instance, how the neighborhood would look and feel if its population density were doubled. No long turnaround times for new drawings, no misunderstandings about what someone said at last month’s meeting.

Especially for those not yet deeply involved with these technologies, this book will serve as a useful introduction. Kwartler and Longo are busy developing and using these technologies, and the book’s illustrations do seem to come disproportionately from their shops (the Environmental Simulation Center and ACP-Visioning & Planning, respectively, both in New York City), but in general they manage to avoid overselling. They aren’t, however, always in a position to offer an outsider’s critique of these technologies. And there are at least four reasons critique is needed:

1. This software is not foolproof. In particular, it works better if it’s part of a good public process. One of the book’s case studies describes how an unnamed “lead consultant” introduced three-dimensional real-time visual simulations only after a good deal of discussion had already taken place, and then didn’t explain them well. As a result, “the workshop participants assumed [not unreasonably] that the 3D walk-throughs were being used to sell the lead planning consultant’s conclusions, rather than to inform the community-based decision-making process.” {74}

2. Like maps, simulations condense a great deal of data and a whole network of assumptions about how different kinds of data fit together. They look concrete but are based on all kinds of abstractions. In this regard, the authors discuss the difference between nonverifiable and verifiable digital photomontages. Verifiable photomontages include information about dimensions, density, floor area by use, number of dwelling units (and presumably the sources of the information) — and are accordingly more time-consuming and expensive to create. “Verifiability becomes important,” they write, “once stakeholders agree that the images are what they like, and then need to understand how to implement them.” But verifiability is always important, given that participants need to be able to check whether the visual impressions being provided are trustworthy. Otherwise there’s plenty of potential for sophisticated deception. The authors acknowledge that members of the public who’ve learned to suspect architectural drawings may not be as wise to 3D simulations. They should be. “These prepathed simulations may involve editing, cropping, and the control of the ‘camera lens,’ and therefore ultimately manipulate the viewer’s experience.” {67}

3. The authors wax eloquent in contrasting the rigid factory-like design of 19th- and 20th-century regulations with newer approaches that “are dynamic, embrace complexity, and respond to the flows of available information in iterative ways.” {63} They like the idea of “just-in-time” planning, conceived on the analogy of Toyota’s production philosophy of just-in-time production of parts. The new software’s fast feedback “suggests the possibility of rethinking the land use regulatory structure — for example, moving from static, predetermined zoning regulations to a development code that is dynamic, just-in-time, and capable of tracking change and evaluating changes against performance indicators.” {67} But what’s just-in-time from the inside can be an unwelcome surprise from the outside. How would a developer respond to discovering that a proposal conforming to last month’s rules is now irrelevant because the rules had been altered by an “iterative process”?

4. Like the advocates of form-based building codes, these authors would like their innovation to end divisive conflict. A good process backed with good technology, they write, “saves time and money, minimizes dissent, creates a positive investment climate, and provides an incentive to elected officials to make tough decisions.” {23} Insofar as many people have mistaken ideas about, say, what a given increased density might look or feel like, this makes sense. But most disagreement about development policy is not based on simple misunderstandings. No community worth having is going to be unanimous about much. The very formulation of the ideal is contradictory: if a community-wide consensus exists, why are the elected officials’ decisions “tough”?

The tools the authors describe are here to stay and to be improved. Future books will hopefully pay additional attention to their political and philosophical implications, and what they can and can’t accomplish.

#